Sunday, October 31, 2010

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

PC Games as "Art," Vol. I: The Catch-33 of Deus Ex

Let's dive right in. I think the most important distinguishing feature of video games is the immersion of the player into the narrative. You, personally, are participating in the unraveling story, not sitting at a comfortable remove as a passive observer. The First Person Shooter (FPS) genre has an easier time achieving this than others for obvious reasons, and the home of the FPS is undoubtedly the personal computer, emerging with Wolfenstein 3D in 1992 and solidifying with Doom in 1993 (it took a full four more years before a console would produce a truly worthy counterpart with GoldenEye in 1997).

Let's dive right in. I think the most important distinguishing feature of video games is the immersion of the player into the narrative. You, personally, are participating in the unraveling story, not sitting at a comfortable remove as a passive observer. The First Person Shooter (FPS) genre has an easier time achieving this than others for obvious reasons, and the home of the FPS is undoubtedly the personal computer, emerging with Wolfenstein 3D in 1992 and solidifying with Doom in 1993 (it took a full four more years before a console would produce a truly worthy counterpart with GoldenEye in 1997).Now, nobody's trying to avoid the honest truth here -- games like Wolf and Doom were conceptual and technical successes only. Their plots can be summarized roughly by a mere handful of words: "Get weapons. Shoot [insert appropriate undesirables here]. Repeat." (The only ambiguity I see here is what exactly I'm shooting at... pixelated vampire-Hitler?) But with their undeniable popularity, these proto-shooters gave rise to a genre that has blossomed into a powerful vehicle for complex narratives. Much as Rapture's lighthouse represents but a narrow portal into the depths of its underwater city, gamers have come to expect not only an entertaining variety of gameplay dynamics in their first-person shooters, but also a wealth of story and character that they experience through that gameplay.

An FPS is possibly the easiest way to get a visceral thrill out of your gaming -- see Omaha Beach in Medal of Honor: Allied Assault or the darkened, demon-infested Mars-base of Doom 3 -- and these are fun and valuable experiences. Lord knows I love to stay up into the wee hours of the night with the lights off and the volume up and scare myself witless with some Doom 3 or Dead Space. But these are still largely reactions you can get from popping in Saving Private Ryan or any (in)decent horror flick. What I want to talk about in this entry are the responses that I think gaming has a unique opportunity to effect.

An FPS is possibly the easiest way to get a visceral thrill out of your gaming -- see Omaha Beach in Medal of Honor: Allied Assault or the darkened, demon-infested Mars-base of Doom 3 -- and these are fun and valuable experiences. Lord knows I love to stay up into the wee hours of the night with the lights off and the volume up and scare myself witless with some Doom 3 or Dead Space. But these are still largely reactions you can get from popping in Saving Private Ryan or any (in)decent horror flick. What I want to talk about in this entry are the responses that I think gaming has a unique opportunity to effect. Ok. Are you still reading? Then you probably realize that a set of problems this massive and complex simply cannot be satisfactorily solved unless you've got a big red "S" stuck to your chest. The key word is "satisfactorily." There are solutions available to you at the end of the game (three, in fact), but none of them are anything but problematic, much less offer you a sure road to human salvation and the obligatory victory cutscene. The brilliance of Deus Ex is that though you are, more or less, a superhero, you cannot save the world. All your extraordinary abilities win you is the chance to get yourself all good and invested in the outcome of the plot only to arrive at a tie between three equally dubious choices.

Ok. Are you still reading? Then you probably realize that a set of problems this massive and complex simply cannot be satisfactorily solved unless you've got a big red "S" stuck to your chest. The key word is "satisfactorily." There are solutions available to you at the end of the game (three, in fact), but none of them are anything but problematic, much less offer you a sure road to human salvation and the obligatory victory cutscene. The brilliance of Deus Ex is that though you are, more or less, a superhero, you cannot save the world. All your extraordinary abilities win you is the chance to get yourself all good and invested in the outcome of the plot only to arrive at a tie between three equally dubious choices.Many games offer the player options; a (sometimes paralyzing) degree of control over your character serves as a supporting pillar of basically every RPG in existence, and several other franchises have also capitalized on player choice as the impetus of plot development (see the Star Wars Jedi Knight series), but these choices are largely relegated to very black and white, good vs. evil situations (do I wantonly slice that hapless bystander with my lightsaber, or... not?). Deus Ex is one of a relatively small contingent of games to thoughtfully, persistently delve into moral territory so grey as to be virtually impossible to navigate. There are no right choices in Deus Ex, only choices.

Of course, we shouldn't praise moral ambiguity simply for its own sake; if we did, we might just as easily prefer characters like, say, the Joker to come out on top instead of Batman, at which point... what's the point? But the complexity of Deus Ex provokes a kind of reasoning that is really only just beginning to be utilized in gaming: ethics. To keep the superhero thread running, who's really going to boo Superman for saving a bus-load of children from toppling off a bridge? He's a stand-up guy, no doubt about it, and that kind of simplicity can be satisfying, too. My favorite novel, The Lord of the Rings, features one of the clearest notions of right and wrong ever put on paper. Clarity is definitely a good thing.

Of course, we shouldn't praise moral ambiguity simply for its own sake; if we did, we might just as easily prefer characters like, say, the Joker to come out on top instead of Batman, at which point... what's the point? But the complexity of Deus Ex provokes a kind of reasoning that is really only just beginning to be utilized in gaming: ethics. To keep the superhero thread running, who's really going to boo Superman for saving a bus-load of children from toppling off a bridge? He's a stand-up guy, no doubt about it, and that kind of simplicity can be satisfying, too. My favorite novel, The Lord of the Rings, features one of the clearest notions of right and wrong ever put on paper. Clarity is definitely a good thing.But consider, in contrast, the conclusion of a film like The Dark Knight, with Batman accused of multiple homicide. It's certainly not the ideal outcome, but the way the characters deal with it says a lot more about them than a knee-jerk reaction to the tired "rescue X from Y" trope ever could. In Deus Ex, it is the player who must react effectively to an unyielding, unforgiving environment, and I think the process of that reaction unlocks not just an exploratory gaming experience, but a self-exploratory one. Isn't that exactly what "art," however we define that almost totally useless term, is supposed to provoke? Explorations like that are vital to our media because they require us to examine and sometimes redefine the beliefs and the values with which we approach the world; they're especially vital to our video games because they continue to prove that this medium can make worthwhile contributions to modern culture.

I digress. Next time, I'll dive into Rapture in search of a little thing called "cultural relevance." Sounds thrilling, doesn't it? I know. I've had Django Reinhardt's "La Mer" on repeat for days in anticipation. (Just for clarity, that's repeat in my head. I apparently can't make it stop.) So, readers -- what other games haunt you with their moral complexity? Any I absolutely can't afford to miss? And yes, I'm already working on Fallout 3.

PC Games as Art: An Introduction

Thus commences a long-planned exploration of the medium that demands (and receives) a massive allotment of my fascination and my imaginative energies. Throughout, I hope to perpetuate, at minimum, the following idea: PC gaming is a valuable medium in modern pop culture, offering complex, entertaining narratives that are (with the rare exception) unique in that they rely entirely on decisions and actions taken by the participant rather than following a predetermined arrangement of scenes and characters. (This is not to say that game plots are not linear; rather, the manner in which they progress is determined by the player rather than the developers.)

Thus commences a long-planned exploration of the medium that demands (and receives) a massive allotment of my fascination and my imaginative energies. Throughout, I hope to perpetuate, at minimum, the following idea: PC gaming is a valuable medium in modern pop culture, offering complex, entertaining narratives that are (with the rare exception) unique in that they rely entirely on decisions and actions taken by the participant rather than following a predetermined arrangement of scenes and characters. (This is not to say that game plots are not linear; rather, the manner in which they progress is determined by the player rather than the developers.) To that end, I will not stoop to arguing why PC games are, in fact, art; at this point in time, I believe the only persons who would actively argue against this are both a) snobbish, likely aging members of academia with a vested interest in keeping a relatively new medium in its place, and b) woefully uncool (see right). Sorry, Roger, but your argument assumes that all other art forms except video games contain no dialogue whatsoever between artist and consumer, which any English major worth his or her student loans will tell you just isn't true. Instead of arguing something that's been successfully argued already, I will provide and discuss examples of PC titles and concepts which prove the point. (And for further discussion on game narratives, check this out.)

To that end, I will not stoop to arguing why PC games are, in fact, art; at this point in time, I believe the only persons who would actively argue against this are both a) snobbish, likely aging members of academia with a vested interest in keeping a relatively new medium in its place, and b) woefully uncool (see right). Sorry, Roger, but your argument assumes that all other art forms except video games contain no dialogue whatsoever between artist and consumer, which any English major worth his or her student loans will tell you just isn't true. Instead of arguing something that's been successfully argued already, I will provide and discuss examples of PC titles and concepts which prove the point. (And for further discussion on game narratives, check this out.)And why PC games, as opposed to video gaming in general? Two reasons. One -- quite simply, I am a PC gamer, and always will be. The personal computer offers a degree of customization and end-user freedom that is and always has been light years ahead of any other gaming platform ever produced. Case in point: user modifications, which simply do not exist elsewhere, not to mention the ability to tweak the game and/or your hardware to achieve the best performance possible for any given title.

Second, I generally regard the PC as the most economical option for today's video gamer, considering that a brand new console from each competing developer emerges every few years and costs $300+, simultaneously rendering the previous ones obsolete, while a single PC can continue to evolve with the technology.

Let me tell you now, the line about PCs being more expensive because they require constant upgrading is a steaming pile of bullshit. I purchased a pretty middle-of-the-road PC in 2006 for about $600 (AMD Athlon 64 3500+, 1GB DDR SDRAM, NVIDIA GeForce 7300 GT, for any who care) and have been happily gaming away ever since. Don't believe me? Check the BIOS date in the pic at the left. Only this past January did I have to add memory and a new video card to play BioShock and Batman: Arkham Asylum, which cost me roughly $100 (Newegg.com ftw!). I have only recently broken down and decided to replace the motherboard and processor, but that's it -- they'll be going straight into the same old casing and hooking up to the same old power supply and hard drive. The cost of maintaining a decent gaming computer is, at the very most, more or less equivalent to purchasing a single brand of consoles (e.g., Microsoft/Sony/Nintendo) over two of their generations (Xbox + Xbox 360, PS2 + PS3) -- except mine runs games and does everything else a PC can do, which means I don't have to drop an additional few hundred dollars just to be able to write this blog post or use a word processor.

Let me tell you now, the line about PCs being more expensive because they require constant upgrading is a steaming pile of bullshit. I purchased a pretty middle-of-the-road PC in 2006 for about $600 (AMD Athlon 64 3500+, 1GB DDR SDRAM, NVIDIA GeForce 7300 GT, for any who care) and have been happily gaming away ever since. Don't believe me? Check the BIOS date in the pic at the left. Only this past January did I have to add memory and a new video card to play BioShock and Batman: Arkham Asylum, which cost me roughly $100 (Newegg.com ftw!). I have only recently broken down and decided to replace the motherboard and processor, but that's it -- they'll be going straight into the same old casing and hooking up to the same old power supply and hard drive. The cost of maintaining a decent gaming computer is, at the very most, more or less equivalent to purchasing a single brand of consoles (e.g., Microsoft/Sony/Nintendo) over two of their generations (Xbox + Xbox 360, PS2 + PS3) -- except mine runs games and does everything else a PC can do, which means I don't have to drop an additional few hundred dollars just to be able to write this blog post or use a word processor.And, on a pleasantly responsible note, the less you replace your electronics, the less you contribute to the problem of conflict minerals, and the less you have to take your old ones to a special recycling center or, worse, commit the wasteful and environmentally harmful act of just tossing them in the garbage.

And, on another responsible note, upgrading your own PC means you will necessarily learn a lot more about how your entertainment devices function, which is never a bad thing.

This is not to say that console games don't have their own positive aspects (in-house multiplayer rather than over the internet and their generally much larger libraries come to mind) -- I just don't plan on discussing them here, except in relation to their PC counterparts.

Well, the day is getting on, and I'm due at work in about an hour, so the "actual" first entry in this series will have to wait. As a teaser, though: I'll discuss the value of moral ambiguity and Really Tough Choices in a medium where all is dependent on player action, via Deus Ex and BioShock. Read up on them so you know what I'm on about.

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Final (and so far, only) comments on The Sopranos

By the way: don't read this if you don't want the finale spoiled for you.

What I mean by the low return on emotional investment is: almost none of the characters show any real development in recompense for our attention and affection over the show's six-year run -- and by "development," I mean change for the better. Again, I'm not disappointed by this; it's one of the things that makes the show so fantastic. As consumers of a fictional story, we have been trained to expect the characters to grow, to improve, or to experience some sort of grand enlightenment as they traverse their precarious tight-ropes. In other words, they should have the proverbial "character arc," as Christopher Moltisanti pointed out to Paulie once upon a time (Chris was right, by the way -- he doesn't have one). With the exception of being slightly less of an asshole for a while after he's shot in the beginning of the sixth season, Tony is the same exact character in the final shot as he is in the series pilot. It's our own fault if we expect anything else -- we are dealing with (arguably sociopathic) criminals, after all.

With that in mind, I find it really ironic that everyone seems so concerned with "what happens" after the show's finale ends. On the one hand, I completely understand the feeling; we don't like not knowing. And, to be perfectly honest, we all develop an affection for Tony despite the fact that he's a murderer (even of friends and family), and so part of us hopes he can pull it together -- both out of genuine goodwill, and the expectation that he should, because this is fiction and that's what happens to the main character.

But there is no character arc, for anybody -- except perhaps pointing slightly downward. Our emotional attachment to Tony is always rewarded with more of the same (making it really easy, by the way, to empathize with many of the other characters on the show). He doesn't keep his end of the implicit bargain that is always present between the audience and the characters. Perhaps on some level, we feel guilty for liking a guy like Tony (and Chris and Sylvio and Paulie etc. etc.), and we want him to change for the better so we could genuinely like him if we knew him in real life.

But he doesn't, so what more can you really ask for in an ending? While briefly rising out of his coma after being shot, he asks Carmela, "Who am I? Where am I going?" The answer is either "nowhere" or "the same place you've always been going." If you think about people in your own life of whom the same is true, people who have had every opportunity to change and who have been repeatedly prodded by friends and family to improve themselves but refuse to do so every single time, eventually the only option is to just disconnect, for your own good.

And yet, a whole lot of viewers complained vehemently about the abruptness of the ending -- it wasn't enough, there were too many loose ends, we needed more of Tony and his mid-life crises and his seedy criminal predicaments. In a brilliantly ironic twist, The Sopranos puts viewers in the shoes of characters like Carmela and Tony Blundetto, who wanted to get away from Anthony Soprano but couldn't, and at the same time manages to get people craving what is so often leveled at TV shows as a criticism -- more of the same.

What I'm saying, basically, is that, right along with the baggage of obligatory affection for fictional "protagonists," I also don't feel like I have any real reason to care what happens to Tony after the screen goes black, whether in a long-term or immediate sense. Ambiguity is perfectly satisfying sometimes.

Other comments:

The tension between safety (family) and danger (the walking Michael Corleone reference) in the final scene is amazing, particularly because the only reason we get anxious while watching it is because we know it's the last episode, and, judging from the clock and the show's subtle cues, we know it's the last scene. If that same sequence had been in the middle of the episode, or a few shows back, it would've been just another dinner out for the Sopranos.

I love it when a movie or a TV show connects a song so strongly with a particular moment that I'll never think of one without thinking of the other again (i.e., "Don't Stop Believin'" by Journey). Other examples that come quickly to mind include "The Power of Love" by Huey Lewis and the News (Back to the Future), "Stuck in the Middle With You" by Stealers Wheel (Reservoir Dogs), and "The Times They Are A-Changin'" by Bob Dylan (Watchmen).

Also, "The Man in Me" by Dylan, in The Big Lebowski (twice!).

Friday, June 11, 2010

Jaws of Unquenchable Thirst -- A Tidbit of Tolkien Ecocriticism

In any case, you know the end of the story, at least generally speaking -- GM didn't learn nothin', and went bankrupt because of it. This episode details the repeated opportunities the NUMMI plant afforded GM, and the repeated, persistent, idiotic refusal of GM's top executives to change their company in ways that could have saved them from, well, its near-death experience last year. In every instance, they were more concerned with the immediate profits of CEOs and shareholders than long-term interests such as sustainable-energy vehicles, better working conditions for laborers, avoidance of Chapter 11 proceedings, etc. The episode is exceedingly interesting, featuring interviews with several high-level managers and executives who were involved with the NUMMI project.

On another car ride recently, this one likely from work to home or vice versa, I was listening to a story on MPR about the coal mine explosion in West Virginia that killed 29 people. Specifically, the radio host interviewed a Mine Safety Expert regarding investigations into Massey Energy Company's safety policies. Once again, the corporation was more interested in its own profit margin than the lives of its workers, even to the point of implying in several memos (but of course not exactly stating outright) that worker safety concerns are always secondary. After all, the money comes from the coal, not from the miners making it out of the tunnels in one piece at the end of the day.

And, of course, there's the catastrophic event of BP unleashing a Balrog* -- er, millions of gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Shockingly, they cut corners and greased up government officials (under the Bush administration, wouldn't you know) in order to swell their coffers. And 11 people died, not to mention the as-yet untold damages to multiple ecosystems upon which thousands depend for their livelihoods. And, you know, the Earth is way prettier when not slicked with the decomposed remains of prehistoric lifeforms, but hell, if they don't care about their sentient employees, who can expect them to give a fuck about a few pelicans?

And, of course, there's the catastrophic event of BP unleashing a Balrog* -- er, millions of gallons of crude oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Shockingly, they cut corners and greased up government officials (under the Bush administration, wouldn't you know) in order to swell their coffers. And 11 people died, not to mention the as-yet untold damages to multiple ecosystems upon which thousands depend for their livelihoods. And, you know, the Earth is way prettier when not slicked with the decomposed remains of prehistoric lifeforms, but hell, if they don't care about their sentient employees, who can expect them to give a fuck about a few pelicans?I guess the solution is: Jesus H. Christ, you oblivious persons and wildlife, stop putting yourself in the path of these few dozen ass-wipes trying to make a buck. Or you know, a few billion that they don't even know what the fuck to do with (Exxon-Mobil continues to be the United States' most profitable company).

In the wide realm of Tolkien criticism (you saw this coming, didn't you?), exploitation of resources in order to consolidate power (i.e., money) is frequently likened to the recklessly destructive actions of Saruman and his minions at Isengard. Indeed, Peter Jackson's film version of The Two Towers goes so far as to have ol' Sharkey saying "the forests will burn in the fires of industry," which to me is about as clear a finger you can point at ecologically irresponsible organizations.

But as we drove home from WI that day (I was in the passenger seat, and thus probably waxing more philosophical than otherwise), looking at some pretty sun rays coming down through dark rain clouds, the concept of these corporations as individual entities (which, according to the Supreme Court, they are) struck me as something else entirely. They don't even seem to be as rational or as deliberate as Saruman was in his machinations to conquer Middle-earth and destroy the natural world in doing so; they seem to me more akin to Carcharoth (also called Anfauglir, the Jaws of Thirst), the watch-wolf at the gate of Angband who, after biting off the hand of Beren that holds a Silmaril, is driven utterly mad by the jewel's power. He rampages all across Middle-earth attempting to slake his now unquenchable thirst, inconsolable and unreachable to logic or reason of any kind, rending apart all who come in his path. The only choice left to Elves and Men is to either slay him or continue to suffer the swath of death and destruction he cuts through the green, living lands of the world.

To quote Théoden, "What can men do against such reckless hate?" The whole thing would be a lot simpler if "ride out and meet them" was the appropriate response, swords a-swinging and a-cleaving. But really, the day at Helm's Deep is saved by the arrival of Gandalf and Théoden's allies -- the key word being "allies," in that unity is required to defeat the hosts of the enemy. Holding true to the comparison, though, the Rohirrim didn't really fight back until all was nearly lost. Such seems the likely outcome in our lives, as well.

Really the answer, I think, is to just wake up the Ents. Or, in the event we can't find any, build some robotic ones, maybe. I think laser beams in their eyes would also expedite the whole process.

*Excuse the slip-up. Crude oil and Balrogs are just so similar. I mean, both are readily flammable, hide in deep underground caverns, and are, according to all evidence, impossible to stop once unleashed. Incidentally, crude oil and Balrogs tend not to cause problems if you just leave them the fuck alone. Just sayin'.

Thursday, June 3, 2010

Brilliant Tolkien Passages, Vol. I

Thus begins what will likely be a very long series of entries in which I'll highlight and comment on a selection from the writings of J. R. R. Tolkien that I find especially insightful, moving, funny, etc.

As some of you may know from the succinct, conveniently-placed "Currently Enjoying" list to the right side of this text, I'm reading through The History of Middle-earth. What you wouldn't know from that conveniently-placed list is that it's the first time I've done so with the express intent of getting through them cover to cover. Retain your gasps, please; it's extremely dense reading at times, particularly if you look at all the endnotes Christopher Tolkien sticks in there. But it's also very rewarding for a Tolkien enthusiast to understand the truly lifelong creative process that went into Middle-earth.

Case in point: this entry's selection, which comes from The Lay of Leithian, the poetic version of the tale of Beren and Lúthien, written in octosyllabic couplets and found in The Lays of Beleriand. In this excerpt from the poem (which, only about three quarters finished, extends over 4000 lines), we are treated to what is perhaps the very first textual appearance and description of Sauron, here called Thû. Beren and (Finrod) Felagund, disguised as Orcs, attempt to sneak past Tol Sirion, an Elvish watchtower now inhabited by Morgoth's servants and called Tol-in-Gaurhoth (Isle of Werewolves). Enjoy!

An isléd hill there stood alone

amid the valley, like a stone

rolled from the distant mountains vast

when giants in tumult hurtled past.

Around its feet the river looped

a stream divided, that had scooped

the hanging edges into caves.

There briefly shuddered Sirion's waves

and ran to other shores more clean.

An elven watchtower had it been,

and strong it was, and still was fair;

but now did grim with menace stare

one way to pale Beleriand,

the other to that mournful land

beyond the valley's northern mouth.

Thence could be glimpsed the fields of drouth,

the dusty dunes, the desert wide;

and further far could be descried

the brooding cloud that hangs and lowers

on Thangorodrim's thunderous towers.

Now in that hill was the abode

of one most evil; and the road

that from Beleriand thither came

he watched with sleepless eyes of flame.

....

Men called him Thû, and as a god

in after days beneath his rod

bewildered bowed to him, and made

his ghastly temples in the shade.

Not yet by Men enthralled adored,

now was he Morgoth's mightiest lord,

Master of Wolves, whose shivering howl

for ever echoed in the hills, and foul

enchantments and dark sigaldry

did weave and wield. In glamoury

that necromancer held his hosts

of phantoms and of wandering ghosts,

of misbegotten or spell-wronged

monsters that about him thronged,

working his bidding dark and vile:

the werewolves of the Wizard's Isle.

From Thû their coming was not hid;

and though beneath the eaves they slid

of the forest's gloomy hanging boughs,

he saw them afar, and wolves did rouse:

'Go! Fetch me those sneaking Orcs,' he said,

'that fare thus strangely, as if in dread,

and do not come, as all Orcs use

and are commanded, to bring me news

of all their deeds, to me, to Thû.'

From his tower he gazed, and in him grew

suspicion and a brooding thought,

waiting, leering, till they were brought.

[Beren, Felagund and Co. appear before Thû, he questions them, and grows still more suspicious.]

Thû laughed: 'Patience! Not very long

shall ye abide. But first a song

I will sing to you, to ears intent.'

Then his flaming eyes he on them bent,

and darkness black fell round them all.

Only they saw as through a pall

of eddying smoke those eyes profound

in which their senses choked and drowned.

He chanted a song of wizardry,

of piercing, opening, of treachery,

revealing, uncovering, betraying.

As noted in a previous post, Sauron (or at least, the figure who occupied Sauron's place in the narrative) was originally a great predatory feline called Tevildo, Prince of Cats. Tevildo was, to be quite honest, comically vain and not terribly bright, and therefore difficult to take seriously -- more like to a crabby house cat than the eventual Dark Lord of Mordor. And though in Leithian his persona has almost completely morphed into the cunning, cruel, and hateful form we recognize, in common with the feline portrayal we still find a curious emphasis on eyes and watching, making it quite apparent that Sauron's primary character element is one that survived almost thirty years of further revision and development, from the writing of The Lay of Leithian in the late 1920s to the publication of The Lord of the Rings in 1954 and 1955. The last three lines, with the repeated use of active participles, especially evoke a relentless gaze from which one cannot hide.

The feline origin of the Tevildo/Sauron character was, of course, not destined to completely die out, as we see in this passage from The Lord of the Rings:

"The Eye was rimmed with fire, but was itself glazed, yellow as a cat's, watchful and intent, and the black slit of its pupil opened on a pit, a window into nothing."

I always find those last four words particularly chilling. And, again, the sorcerous power to uncover all that is hidden:

"The Eye: that horrible growing sense of a hostile will that strove with great power to pierce all shadows of cloud, and earth, and flesh, and to see you: to pin you under its deadly gaze, naked, immovable."

I read once that Tolkien's editors/publishers were wary of a novel in which, after hundreds of pages leading up to a decisive moment with monumental implications (i.e., All Lands Covered in Darkness or... Not), there is no direct confrontation with the Enemy. But it is precisely this aspect of Sauron in The Lord of the Rings that allows him to function as such a terrible force: he cannot be faced directly, and thus he remains a mystery beyond all our power and our knowledge -- literally a shadow.

And lastly, an image of Sauron painted by Tolkien himself:

Monday, May 17, 2010

A Brief Letter to Amarthiel, "Champion of Angmar"

I'm not sure which Seeing-stone you got your grubby hands on, but please be informed that it cannot, in point of fact, be the Osgiliath-stone, which was far too large for one person to carry, and is in any case lost at the bottom of Anduin. Either sort your shit out and decide it's one of the other stones that somebody somehow fished out of the bottom of the Ice-bay of Forochel, or I'll not only kick your ass next time we meet, I'll also proceed to delete all files containing your name from my hard drive for your blatant disregard for the Tolkien canon. kthanks.

Love,

Haldaran Casarmacil, Protector of the Shire

Wednesday, May 12, 2010

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT

Remember that next time your feline "friend" sits on your lap and purrs, or watches you with eyes glowing in the dark. He's probably plotting to overrun the world with his wicked servants and enslave you.

Saturday, April 24, 2010

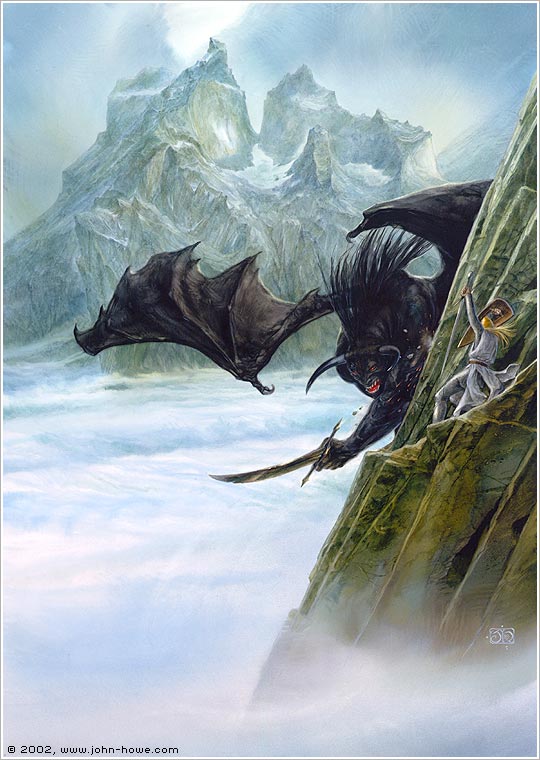

Wings or No Wings -- That Is Not the Question

Anyway, according to The Encyclopedia of Arda, this single question receives more user input than any other of the literally hundreds of entries on their site -- to such an extent that they have devoted several pages to the discussion of whether a Balrog has wings, whether they can fly (assuming they have wings), whether they can change shape and size at will (in order to accommodate both sides of the argument), etc. The subject has inspired scholarly essays, full-length book chapters, and a general feeling of chaos and uncertainty among Tolkien enthusiasts. If we don't know whether a Balrog has wings, then gosh darn, is there anything we can really know for sure about Middle-earth?

Anyway, according to The Encyclopedia of Arda, this single question receives more user input than any other of the literally hundreds of entries on their site -- to such an extent that they have devoted several pages to the discussion of whether a Balrog has wings, whether they can fly (assuming they have wings), whether they can change shape and size at will (in order to accommodate both sides of the argument), etc. The subject has inspired scholarly essays, full-length book chapters, and a general feeling of chaos and uncertainty among Tolkien enthusiasts. If we don't know whether a Balrog has wings, then gosh darn, is there anything we can really know for sure about Middle-earth?To start -- most coherent essays on this issue that I've read conclude that, based on painstakingly nit-picky considerations of what constitutes a metaphor, Balrogs probably don't have wings in the same sense as, say, the Great Eagles (see: deus ex machina), or the Nazgûl's flying beasts. To the No-Wings camp, this seems to justify the belief that Balrogs are utterly bereft of any sort of scary adornments attached to their backs, doomed to wander the darkened halls of Moria or Who-Knows-Where wearing an immortal sadface for their inability to take to the skies. (No-Wings folks don't seem to raise any stink about visualizations of Balrogs with tails, despite the fact that Tolkien never used the word "tail" in reference to them.)

But just like the camp that says they do indeed have actual, honest-to-goodness wings, that interpretation takes a flying leap in reaching its conclusion. One thing is (almost) certain: Balrogs don't fly. At least, we should assume this is true considering they fall to their deaths often enough that, if they could fly, they'd also have to be abysmally stupid (pun absolutely intended). But it is still entirely plausible that they might have wings, if only of a shadowy, ethereal sort. Why? Because they're servants of Morgoth, and as such, there's one thing they enjoy doing above almost anything else -- looking scary.

Think about the most descriptive passages concerning what may or may not be wings on a Balrog:

and

'...suddenly it drew itself up to a great height, and its wings were spread from wall to wall...'

This argument has been made before -- i.e., "A Balrog can have wings if it wants to have wings, because it's a lesser god and they do what they want." Well... cosmetic, non-functional, scary-as-hell wings, definitely.

Further, let's think about Tolkien's use of his languages, as we always should. Their names in both Sindarin and Quenya mean "demon of power." How do most people in the western hemisphere imagine a demon? Granted, there are many, many possibilities -- even a cursory glance at Wikipedia's page on demons reveals "demonology" to be a massive and convoluted subject (almost certainly more so than Tolkienology). However, my guess would be that a majority of people would describe a large, man-like creature with beastly features, horns, and wings, à la Lucifer and many other Christian visualizations of fallen angels (which, by they way, is more or less what Balrogs are). Search Google Images and see what comes up.

To my extensive (but necessarily incomplete) knowledge, Tolkien does not use the morpheme for "demon," in any of his languages, to collectively describe a class of creatures other than Balrogs. "Orc" can also mean "demon" in his Elvish tongues, but it also carries other connotations, and as far as I can tell, "rog" in "Balrog" and "rauko" in "Valarauko" are not etymologically related to it. ("The word [orc] is, as far as I am concerned, actually derived from Old English orc 'demon', but only because of its phonetic suitability" -- the author, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien) Regarding his use of the morphemes "rog" and "rauko," though, this might be an indication that "demon" meant something fairly specific to him, especially considering that, despite being a devout Catholic and acknowledging The Lord of the Rings as a "fundamentally religious" work, he almost always avoided using words or concepts with any strong Christian connotations. Once the reader becomes aware of the meaning of the creature's name, it seems nearly unavoidable that many should imagine it with wings, or at the very least, extremely wing-like forms expanding behind it.

To my extensive (but necessarily incomplete) knowledge, Tolkien does not use the morpheme for "demon," in any of his languages, to collectively describe a class of creatures other than Balrogs. "Orc" can also mean "demon" in his Elvish tongues, but it also carries other connotations, and as far as I can tell, "rog" in "Balrog" and "rauko" in "Valarauko" are not etymologically related to it. ("The word [orc] is, as far as I am concerned, actually derived from Old English orc 'demon', but only because of its phonetic suitability" -- the author, The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien) Regarding his use of the morphemes "rog" and "rauko," though, this might be an indication that "demon" meant something fairly specific to him, especially considering that, despite being a devout Catholic and acknowledging The Lord of the Rings as a "fundamentally religious" work, he almost always avoided using words or concepts with any strong Christian connotations. Once the reader becomes aware of the meaning of the creature's name, it seems nearly unavoidable that many should imagine it with wings, or at the very least, extremely wing-like forms expanding behind it.Fortunately for the casual fan, but unfortunately for us Wing-Agnostics, Tolkien was actively against forcing a single, particular meaning on the reader. His primary interest was to entertain with an enjoyable fantastical narrative, and he frequently indicated his displeasure with both over-analysis of a text to the point of meaninglessness ("He who breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom" -- Gandalf), and with the "tyranny" of authors who intentionally fashion a story so as to deny any freedom of interpretation. See The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien for many examples of this sentiment, as well as the Foreword to The Lord of the Rings.

My final conclusion, then, is basically an altered version of an above statement: Balrogs (almost certainly) don't fly, but a Balrog can have wings if you want it to have wings, because Tolkien was an author who wanted you to enjoy the story to its fullest. My Balrogs have wings of shadow because I think they look more intimidating and evil that way, and that enhances my enjoyment of Tolkien's writing. Tolkien was vague about the appearance of Balrogs -- probably intentionally, what with the whole "cloaked in shadow" thing. It's a fact we should face with excitement rather than frustrated deliberation.

As of two days ago, I have a much more important question on my mind. Balrogs: hosts or a handful? The answer could change my visualization of an entire age of Middle-earth.

Monday, April 12, 2010

A Postcard from Middle-earth

So I haven't been around Sure as Shiretalk the last week or two, and I'll tell you why: over the weekend of March 27-28, The Lord of the Rings Online offered a $9.99 deal for the Mines of Moria and Siege of Mirkwood expansions plus 30 days of free play. So I've returned to Middle-earth in the guise of Haldaran Casarmacil, Protector of the Shire (I love the title system in LotRO). You'll be happy to know I've leveled up four times since then; I'm currently sitting about halfway to level 43.

What I love most about this game is how incredibly true to the novel it feels. I've played most of the LotR-based games out there, and most of them are forced to sacrifice much of the subtlety and restraint employed by Tolkien -- espeically regarding the use of "magic" -- in favor of, presumably, attracting and entertaining a wider audience than die-hard Tolkien fans (why this "wider audience" requires all that flashy Magic Missile bullshit to be adequately entertained is entirely beyond me). But if not for Gandalf very occasionally creating fire or lighting his staff up like a lamp, The Lord of the Rings would be basically devoid of overt displays of supernatural power. Most of Middle-earth's magic is in the land, in the creatures that inhabit it, and in the interactions between good and evil intentions -- most emphatically not at the end of a wand or the tip of somebody's fingers.

Unlike titles such as The Third Age (a Final Fantasy clone with flashy spells for every class) or The Two Towers/The Return of the King (aka Dynasty Warriors in Middle-earth), LotRO keeps the offensive magic and flashy sword-and-sorcery nonsense to the minimum necessary, and finds ways to work it into the game that effectively maintain Tolkien's vision. Players have Morale rather than Health; you retreat to a rally point rather than die and get resurrected. Consequently, your hitpoints are affected by abstract stimuli, most notably fear, as well as the common orc-sword. For example, should you encounter a great source of terror like a Ringwraith or a dragon, you take a noticeable hit to your total number of HP (which is then removed when you either defeat that enemy or remove yourself from its presence; there are of course many ways to partially/completely counteract these fear effects). Accordingly, then, the "healer" class is a Minstrel who keeps his/her allies in the fight by inspiring them instead of performing on-the-spot surgery and blood transfusions.

Beyond that, the storytelling also feels very Tolkienesque; although I'm sure his perfectionism would've found countless things to disagree with, the quests and "Epic" plotline feel close enough to his style and sensibilities that a Tolkien fanatic/purist like myself can really enjoy the feeling of (near) total immersion in Middle-earth and its cultures.

Beyond that, the storytelling also feels very Tolkienesque; although I'm sure his perfectionism would've found countless things to disagree with, the quests and "Epic" plotline feel close enough to his style and sensibilities that a Tolkien fanatic/purist like myself can really enjoy the feeling of (near) total immersion in Middle-earth and its cultures.

One final comment: I cannot express how beautiful and how detailed this game is. When I first started playing, I wandered off to Weathertop to check out the scenery, and when I got to the top, I checked for the rock with Gandalf's runes written on it. It's there. Even locations that Tolkien left with almost no descriptions are startlingly, awesomely depicted. My jaw dropped when I first set eyes on the massive tower of Annúminas on the shores of Lake Evendim; Rivendell nearly broke my heart with its autumnal splendor; the Shire is every bit as charming and peaceful as you'd expect it to be.

In other words, I love this game. It's a brilliant rendering of my favorite novel of all time.

Last comment: I've also loaded up the GoldenEye 007 again recently. God this game rocks my socks.

Friday, March 26, 2010

Hollywood Badass of the Day -- Michael Biehn

Kyle Reese, The Terminator

So here's a guy who, after spending most of his life scrabbling through the nuclear wasteland of what used to be Los Angeles, decides "Hey, I'm gonna test pilot this brand-spanking-new time travel equipment we jacked from SkyNet." Nevermind that he had no way of knowing whether it worked or if he wasn't going to be splattered into a million pieces all over the time-space continuum. He did it anyway. Then, using "stone knives and bearskins" (Spock's assessment of 20th century technology) he fends off a T800, escapes from the LAPD, and procreates the savior of humanity with Sarah Connor all in one day (er, that last one without the stone knives and bearskins, I think).

Also, near the end of the film, he goes melee with the Terminator using only a steel pipe, saying, "Come on, motherfucker." Whatever else you say about him, the guy's got balls.

Key quote: "Come with me if you want to live."

Corporal Dwayne Hicks, Aliens

Yeah, he might mostly be the same character as Kyle Reese, but he's still a badass, and he survives the constant shit-hitting-the-fan that is the movie Aliens. Only two other humans and half an android managed that. Hicks makes it through because he keeps his cool. When Hudson's all like "Game over man! Game over!" Hicks is like "...Are you finished?" And then when they find out Burke was going to murder them on the way home, he's like "All right, we waste him. No offense."

Key quote: [pulls out his pump-action shotgun] "I like to keep this handy. For close encounters."

Johnny Ringo, Tombstone

Only Biehn and Val Kilmer can master this mustache and not look totally ridiculous. Hell, Biehn even manages to look genuinely mean in it. He has this tense, brooding presence throughout the film that always provides the bite to Curly Bill's bark. He's a stone-cold killer who jokes about death and displays zero remorse for any of his rather shocking actions.

Key quote: As Wyatt and Virgil Earp drive their brother's casket to the cemetery, Ringo mutters, "You smell that, Bill? Smells like someone died."

He's also starred as Michael McNeil in Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun alongside James Earl Jones, and apparently it's rumored that he might show up in 2011's film version of Kane and Lynch. Food for thought, people. In the meantime, go watch one of these movies.

Deathmatch -- Aliens vs. The Terminator

Deathmatch #2 here at Sure as Shiretalk has come around, and this time we're featuring a pair of sci-fi favorites in contrast to last time's fantasy characters. This one came up between my roommates and I after I purchased the first three Alien films recently. So, here it is: Aliens vs. The Terminator. Let's meet the combatants.

Disclaimer: I have not read, nor do I intend to read, the comic titled "Aliens versus Predator versus The Terminator."

Cyberdyne Systems Model 101, The Terminator

"That Terminator is out there. It can't be bargained with. It can't be reasoned with. It doesn't feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop. Ever. Until you are dead."

Thus spake Sgt. Kyle Reese to Sarah Connor concerning her pursuer in 1984's The Terminator. The T800 is a highly intelligent sentient computer system housed inside a humanoid titanium alloy combat chassis. Virtually invulnerable to projectile weapons, this model Terminator basically needs to be decapitated before you can be sure it's done for -- or you at least need to make sure you smash that computer chip in its head.

Also, the Arnold version wears shades, rides a Harley, and wields a shotgun one-handed.

The Xenomorph, Alien

The Xenomorph, Alien"You still don't understand what you're dealing with, do you? The perfect organism. Its structural perfection is matched only by its hostility... A survivor, unclouded by conscience, remorse, or delusions of morality."

Ash was certainly right about that in 1979's Alien. An organism that can survive intense heat, cold, and the vacuum of space without showing any signs of discomfort is certainly more structurally perfect than most. Nevermind that it has molecular acid (<-- not real, btw) for blood, which can apparently eat through basically any substance in moments (but takes considerably longer with Michael Biehn's skin... what a badass). They're also great predators, meaning they're stealthy, strong, and quite a bit smarter than your average bear.

Well, let's assume a couple of things: the Terminator is armed, and there are multiple Aliens. I hope we can all agree that, should the Terminator gain a vantage point from which he is more or less inaccessible, he wins by pumping them all full of hot lead. The Aliens are apparently vulnerable to normal gunfire, and a few good shots generally takes them out, acid blood a-splashing every-goddamn-where. Up close and personal might be a different story, though.

Given that the Terminator is made of titanium, I'm going to go ahead and say that skull-bashing thing from the Aliens' jaws-inside-the-jaws is just going to break some teeth. They also probably won't be able to do a lot of damage with their claws or that spiky tail, again because Terminators are pretty much solid as a rock.

However, in order to kill any of them, the Terminator is probably going to have to start breaking some skin, and that could lead to some serious battle damage. Like, Arnold-at-the-end-of-T2 battle damage. If he gets mobbed, the Aliens might be able to use their combined strength to just yank him apart, which would of course render him immobile and therefore defeated. Whatever the case, it would be an epic battle worthy of multiple Aliens versus The Terminator films regardless of how increasingly bad they might get.

So, Terminator wins, but with ever-decreasing odds the more Alien blood he spills. Sorry, Aliens, but you're just not quite as perfect against inorganic opponents. [insert xenomorph sadface here]

Btw, I love this picture, and I want to see the movie right now:

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Top Five Most Reprehensible Corporations in Science Fiction

This post was inspired by a page out of this April's Game Informer magazine. There are plenty of evil corporations in gaming, of course, but some of the worst of the worst come from films as well. I'm also a bit peeved about GI's picks -- a few of them, such as Aperture Science (Portal) and Union Aerospace Corporation (Doom 3), seem to conflate the corporation itself with a single person (or in Portal's case, a single AI). In light of my disagreements, I've used the word "reprehensible" in my title so I can highlight some of those discrepancies between the corporate and the individual entities.

Weyland-Yutani Corporation, Alien

This corporation, generally referred to as "The Company" (indicating its sheer size and realm of influence), apparently finds it morally acceptable to impregnate its employees with chestbursters in order to acquire the Alien for their biological weapons development. So, disregarding the very real possibility that a single xenomorph could wipe out the human race, let's reverse-engineer these nasty buggers just so we can kill some stuff.

Who did they want to kill, anyway? I can't recall a single instance in any of the Alien films where they mention being at war with anybody.

VersaLife and Page Industries, Deus Ex

VersaLife and Page Industries, Deus ExWhat's worse than manufacturing an extremely aggressive mechanical virus with a 100% mortality rate? Profiting from the cure. Under the direction of Bob Page and Walton Simons, VersaLife could have destroyed human life on Earth -- all in the name of shameless power-grabbing and greed.

Typical behavior from billionaire Majestic-12 puppeteers, I suppose.

Well, Dr. Betruger, that's who. UAC is partially responsible because there had to have been somebody who could guess at what he was up to and possibly have prevented it. Just think of all the ventilation shafts we could have stayed the hell out of if not for that wacko...

Fontaine Futuristics, BioShock

and BioShock 2

and BioShock 2So this classy bunch has no qualms with abducting little girls and subjecting them to ghastly physical and psychological conditioning to further the goals of a sociopathic conman and, after he was dead, a deranged political extremist. Oh, and they worsened the Rapture Civil War by increasing the supply of the very substance that drove everybody insane. So in essence, they are the persons most directly responsible for all of the things that want to kill you throughout the entirety of BioShock and BioShock 2.

On the upside, though, they did produce the Big Daddies, meaning you get to Drill Dash countless hordes of poor splicers into the walls. Oh the joy, after being so slow and cumbersome for the first couple hours of the game.

Multi-National United, District 9

Same story here as Weyland-Yutani, really -- experiment on living organisms to create bigger and badder weapons. Except the prawns are far less hostile than the xenomorphs, as they're more or less a metaphor for oppressed racial and ethnic groups of South Africa.

They've also got a paramilitary organization backing them, which is never a good thing when it comes to amoral corporate entities.

Science Fiction -- A Discussion of Defintion

It has frequently been brought to my attention in the past few months or so that our society at large is disturbingly unclear on what constitutes the genre of science fiction. For serious, people, this has got to stop.

It has frequently been brought to my attention in the past few months or so that our society at large is disturbingly unclear on what constitutes the genre of science fiction. For serious, people, this has got to stop.There is no single way of saying it that highlights all of the aspects of the genre, but one thing I am certainly tired of is people assuming something is science fiction just because it involves spaceships or laser guns. A look over Wikipedia's article will tell you sci-fi is "realistic speculation about possible future events, based solidly on adequate knowledge of the real world, past and present, and on a thorough understanding of the nature and significance of the scientific method." That's a pretty good starting place regarding setting, but it's also extremely vague, and it doesn't really touch on what kind of themes we should be looking for, either.

I would complicate the above quote by adding the following: "Science fiction seeks to discuss the portent for humanity of these possible future events, including but not limited to the consideration of ethics, morality, longevity/survivability of the species/our native planet, and the implications thereof for modern humanity. The genre frequently chooses to remain morally ambivalent about said considerations; on the other hand, it also frequently uses the depiction of possible futures to warn or admonish the audiences of today."

In order to demonstrate the definition that I've laid out thus far, I think a comparison of two well-known and well-loved films is called for. One is a near-perfect example of science fiction at its best, and the other (while a great film in its own right) is often mistakenly judged as part of this genre.

In my experience, The Terminator (1984) is regarded either very well or very poorly (in the same categories respectively, you generally find people who have seen it and people who haven't). Judgments of quality notwithstanding (I happen to love this movie), it is a prime example of many different plot devices and themes often employed by the genre -- namely, time travel, artificial intelligence, nuclear holocaust, and the human ambitions that bring these situations about. The film elicits sympathy for Sarah Connor and Kyle Reese as they suffer the results of actions entirely beyond their control.

Star Wars places far more emphasis specifically on morality and conflict themselves rather than the issues that inform and cause them. This may seem like a relatively negligible difference, and yes, some titles blur the line in really cool ways, but consider this: What would Star Wars be without the intense division between good and evil? It is those two forces that shape the film's plot and create the galaxy-spanning civil war that culminates in Return of the Jedi. I would argue that one of the reasons we enjoy Han Solo so much is that we're able to see and identify with his progression from selfish mercenary to swashbuckling hero -- but how much would we like him if he had ended up on the other side? (Think about how you feel when Lando Calrissian cooperates with Vader.)

The myriad alien races, the dogfights in space, and the advanced technology of all kinds add an exoticism to the film that enhances its appeal and originality, but in its thematic focus, Star Wars is far more similar to The Lord of the Rings than other sci-fi titles involving space travel, such as 2001: A Space Odyssey or Battlestar Galactica. Star Wars is a morality play that emphasizes the dichotomy between good and evil as the defining conflict in the very fabric of the universe. Space fantasy, if you will. Science fiction (at its most interesting, in my opinion) tries to avoid such sweeping statements in favor of complexity of character and ambiguity regarding difficult and often undesirable situations.

None of this is to say, however, that certain titles do not significantly blur the lines between sci-fi and many other genres -- some of my favorites being Firefly, Serenity, and Back to the Future. On the contrary, it becomes easier to identify these blendings of genre when we have a clear notion of what we're talking about when we say "sci-fi" or "fantasy."

So, next time you hear someone say that Star Wars is the greatest sci-fi movie of all time, tell them they're wrong.

Friday, March 12, 2010

Midtown Global Market FTW

Sci-fi badass of the day brought to you by: Sigourney Weaver.

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

Exciting Pseudo-News from the World's Slowest Game Developer

The Ethics of Digital Rights Management vs. Software Piracy

So gamers everywhere are a bit peeved (oh who am I kidding, they've already collected the torches and pitchforks) over the new version of digital rights management (DRM) software shipping out on the PC port of Assassin's Creed II, the console versions of which have received rave reviews for slick, atmospheric gameplay and more finely-tuned mechanics carried over from the original. UbiSoft, on the other hand, is getting the proverbial vegetable justice for the unprecedentedly stringent anti-piracy software required to even install the game, much less play it.

A brief rundown on DRM software: anti-piracy measures originated as little more than a coding trick to prevent users from copying the game CDs or DVDs; since these are typically required to be in the computer's CD/DVD-ROM drive during play, this method prevents your average consumer from buying a single copy and distributing it for free to all his/her friends. More recently, publishers have started requiring users to register the software online, which "unlocks" the game on your computer (Steam and Games for Windows Live are a couple of examples). Combined, these methods effectively prevent most of the population from actually initiating any software piracy, but that's of little consequence when a small percentage of those people can "crack" the game and make it available for download to anyone with an internet connection.

Assassin's Creed II is taking anti-piracy to a whole new level. Besides the by-now obligatory internet activation, PC gamers will be required to be connected to the Internet at all times during play. If your connection goes out for longer than a few seconds, all progress since the last checkpoint in the game will be lost.

What I want to address in this post is the extremely awkward and unpleasant position in which most PC gamers now find themselves, should they want to play recent and upcoming games. We are either forced to acquiesce to such blatantly ridiculous anti-piracy measures, or start illegally downloading our games.

Before I get into that, though, I'll explain why it's ridiculous. Time was when I could walk into a store, purchase an item, take it home, and use it. End of happy capitalist consumer story. But not anymore. Let's say I want to go into GameStop or wherever and buy a copy of BioShock 2 or Batman: Arkham Asylum. When I take it home, the game is unplayable until I've asked permission from Windows Live to use my legally purchased product. Apparently exchange of currency is no longer enough to get you certain retail items in this society built on rampant capitalism. Much as I despise that economic system most of the time, I must say that not having complete control over something I've paid a decent chunk of cash for (currently about $50 and rising for a new PC game) really, really pisses me off.

Further, it cannot be said under any circumstances that video game developers and publishers are doing anything other than raking in the money hand over fist. Grand Theft Auto IV, the most expensive video game ever made, cost $100 million. It generated $500 million in the first week after it was released. It has apparently shipped 13 million copies worldwide, which, if we do a little simple math at 50 bucks a pop, brings the total up to $650 million.

Returning to ACII, which has only been released on Xbox 360 and the PS3 so far, we find it has sold roughly 8 million copies as of February 10 this year. A little more math (this one costing $60), and we get a total of $480 million. UbiSoft is apparently a little cagey about their production costs, but if we go with high-end numbers from this article, ACII probably did not cost UbiSoft more than $34 million. Let's see... that's a profit of 446 million dollars, which is a higher net profit than 17 of the 20 most profitable films of all time (only The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Titanic, and Avatar have had a better turnaround). Assassin's Creed II has only been out since November, and the PC version still hasn't been released. Here's my general feeling toward UbiSoft on the subject of software piracy:

I'm so sorry, UbiSoft, I didn't realize you had fallen on such hard times. Please, let me shell out 60 dollars, which is between 15-20% of my average paycheck, in order to play (but not physically own) a game that has made more money for you in four months on only two of its three systems than Jurassic Park did for Universal in its entire run through movie theaters. Piracy is pretty much only possible on PC versions of video games, and as we know, they're certainly not hurting for console sales. What's really at stake then, if not their company's survival? I think this whole thing is about property. The fat cats of video gaming are pissed off that some guy (who likely knows more about computers than they ever will) can sit in his room at home and alter the software so that it can be used without paying their increasingly exorbitant prices.

Okay, okay, enough sarcasm and simple arithmetic. I believe, as many do, that video games are just as much an art form as books, music, films, and television programs (the extremely variable quality of these is not currently under discussion), and as such, their creators do indeed deserve reasonable compensation for their efforts. All of these media (except PC games) are available to me in some fashion for free or for a small fee before I actually have to pay to own them -- which is a good thing, because it's extremely disappointing to spend one's hard-earned money on some form of media only to find out that it sucks. (Case in point: since I didn't get to the theater in time, I am the unfortunate owner of The Matrix Revolutions.) Instead of spending stupid amounts of money developing more and better DRM software, which is guaranteed to alienate honest PC users and only slightly more likely to confound pirates, why not develop a system in which PC gamers can test-play a game before we have to buy it? Or perhaps figure out a way that we could play a game only once before having to pay the full amount, like seeing a movie at the theater vs. buying the DVD? I'd be fine with UbiSoft's new technique if, say, it was significantly cheaper and good for only a single playthrough -- provided I could later purchase the game, permanently, in its complete form (no bullshit Internet connections required).

Demos do not count toward this end, and I'll tell you why. If I was given a demo of the original Assassin's Creed, containing only the first couple of levels, I would probably run out and buy the game right then and there; I mean, in the first hour of play, the game appears to be truly amazing. What a demo wouldn't tell you, though, is that the game is extremely repetitive through its entirety and downright annoying by the last hour or so. I know this from recent experience, and as a consequence I will not be buying the game. On the other hand, I played through Arkham Asylum once and purchased it immediately afterward. Like I said, good work deserves good compensation. Another good example: I recently played BioShock for the first time, too, and I plan on buying it myself at some point. In any case, my point is that I should not have to pay money for something that I won't like, and at this point in time, there is no way for a PC gamer to make that determination aside from a) borrowing a game, or b) downloading it illegally. That needs to change.

Granted, these methods still probably wouldn't stop piracy, but then, it seems unlikely that anything ever will. What it would do is retain PC gamers' trust, and, ideally, encourage developers to produce games that are so good, gamers will want to spend their money.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

Faster than a speeding bullet, and almost as unique -- Enemies & Allies by Kevin J. Anderson

I'm a sucker for all things Batman. You guys know that. So when my uncle got this book from the fam for his birthday last year, I was intrigued (I borrowed it from him because I'm poor and cheap and I generally shy away from buying things I'm not absolutely sure I'll like). I also really enjoy pretty much anything about the UFO scares of the 40s and 50s (hence why I liked Kingdom of the Crystal Skull more than others seemed to), and I find the Man of Steel tolerable, and sometimes even interesting, when he's juxtaposed with the Dark Knight. And besides, the only other Batman novel I'd read was No Man's Land, which was suspiciously, annoyingly lacking in Batman (as were the original comic versions). I was also psyched for another novel by Kevin J. Anderson, whom I had read and liked long before for his work in the "Star Wars Expanded Universe" or whatever they call the non-canon (and therefore good) Star Wars lore these days. I was hoping the late 50s setting would add some new interest to the meeting of two superheroes who tend to run into each other in the comics almost as often as Clark Kent runs into kryptonite on Smallville.

I'm a sucker for all things Batman. You guys know that. So when my uncle got this book from the fam for his birthday last year, I was intrigued (I borrowed it from him because I'm poor and cheap and I generally shy away from buying things I'm not absolutely sure I'll like). I also really enjoy pretty much anything about the UFO scares of the 40s and 50s (hence why I liked Kingdom of the Crystal Skull more than others seemed to), and I find the Man of Steel tolerable, and sometimes even interesting, when he's juxtaposed with the Dark Knight. And besides, the only other Batman novel I'd read was No Man's Land, which was suspiciously, annoyingly lacking in Batman (as were the original comic versions). I was also psyched for another novel by Kevin J. Anderson, whom I had read and liked long before for his work in the "Star Wars Expanded Universe" or whatever they call the non-canon (and therefore good) Star Wars lore these days. I was hoping the late 50s setting would add some new interest to the meeting of two superheroes who tend to run into each other in the comics almost as often as Clark Kent runs into kryptonite on Smallville.Well, despite the fact that Anderson sends both Batman and Superman to exotic locales such as Siberia and Area 51, the heart of all UFO conspiracy theories, there was almost nothing new or interesting about any of their interactions. Even in the key moment, when they meet each other for the "first time" (how many times can that happen in one universe, anyway?), Anderson can't seem to think of any scenario other than what has probably been written a hundred different times by as many authors since the late 1930s: Superman is all hands-on-his-hips, spouting his "halt evildoer" nonsense, and Batman is gruffly having none of it and disappearing into thin air. Oh, and the dialogue is flat and fails to say anything worthwhile about any of the super important differences between the two characters.

Sigh... So you just biffed the most anticipated moment in your epically-staged but disappointingly-executed novel about the two most popular superheroes in history. Any reason I should read on instead of picking up The Dark Knight Returns again to wash the awful taste from my mouth? I guess I couldn't really think of one at the time, but I kept going anyway (I'm apparently just loony enough to stick it out to the bitter end, but sane enough to be irritated with myself afterward). Lex Luthor is the supervillain for this go-around, and he's without doubt the most enjoyable figure in the novel. Anderson does get the character right here; Superman's nemesis is quite sufficiently despicable, and his final line in the book almost makes it worth the three or four hours (tops) it'll take you to read it.

Anyway, the whole thing comes off as more of an outline in need of serious expansion and revision than a complete, polished novel. I would've welcomed another few hundred pages if it meant the story would be long enough (and good enough) that I'd actually have the time to get invested in it. And, though this is certainly personal preference speaking, more Batman is never a bad thing. But as it stands, the entire novel zips by about as fast as the Man of Steel rushing to save Lois Lane falling off whichever tall structure she decided to climb today, and you're not going to find any situations or sentiments here that aren't better said somewhere else in the vast DC canon. Take a look at this .gif about these two bruisers of comic books instead of reading Enemies & Allies -- it'll save you some time, and it's definitely more enjoyable.

2 stars of 5.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

My Top Five Most Memorable Video Game Showdowns

One of the most common scenarios is the standard FPS approach, in which the player might have less innate power than their foe, but can sure as hell shoot bigger guns at them -- see Doom 3 or Return to Castle Wolfenstein. When that doesn't work, perhaps because the enemy is invulnerable to normal attacks, you can let the player in on a secret weakness that they can then exploit (see any number of platformer games; check out Portal for a really unique FPS example). This last one seems more common to me, probably occurring more often for the sake of adding variety to a game. There are a few other possibilities for how we gamers can defeat the big bad bosses, but they usually fall into one (or both) of those general categories.

However, that's not what I'm interested in right now. The confrontations I'm looking to record here are the ones that really stick with you for reasons other than their difficulty or originality. I'm looking for those showdowns that you'll remember forever not only because of the showdown itself, but also for the build-up to it and the characters involved. My examples will be biased in favor of PC games since that's what I play most; they'll also likely not include anything from more strategy-based genres, because I want to focus more on the you-against-the-world/mano-a-mano sorts of battles. So, these are listed basically in the order that they occurred to me.

JC Denton vs. Walton Simons, Deus Ex

The world economy is falling apart around you. A man-made disease is killing off millions needlessly. You're stuck in the bowels of a defunct deep-sea base, fighting off irritating little poison-spitting lizard-birds, the result of some mad scientist's genetic experiments ("Green greasy greasels!"), and all the wh

ile some slimy-voiced douche-bag pipes his narcissistic plans for world domination straight into your brain. Where in god's name is the fucking mute button on this InfoLink!? Well, you're in luck, because said power-hungry creepo Walton Simons is coming to stop you escaping from the base, and his smug ass is definitely not armed well enough to handle JC Denton. At last, you get to reap your sweet revenge for all his angsty, meaningless rantings about you foiling his plans thus far. Generally, I find a good slice or two with the Dragon's Tooth sword most satisfying.

ile some slimy-voiced douche-bag pipes his narcissistic plans for world domination straight into your brain. Where in god's name is the fucking mute button on this InfoLink!? Well, you're in luck, because said power-hungry creepo Walton Simons is coming to stop you escaping from the base, and his smug ass is definitely not armed well enough to handle JC Denton. At last, you get to reap your sweet revenge for all his angsty, meaningless rantings about you foiling his plans thus far. Generally, I find a good slice or two with the Dragon's Tooth sword most satisfying.Why is it memorable? Because Walton Simons is an affront to all that is good and noble in humanity, and you, a genetically-modified, nano-augmented superman, have the power to splash his guts all over the goddamn underwater cavern (or Area 51, depending on your choices), thus putting an end to the military head of one of the most dastardly plots ever devised to take over the world. I kid you not, the first time I killed him, I got up out of my chair, pointed viciously and shouted at my computer screen: "Eat shit and die, you smug. fucking. bastard."

Death Egg Zone, Sonic the Hedgehog 2

I particularly appreciate Sonic standing there all hands-on-his-hips glaring at a giant doomsday robot. Surely one of the eternal badasses of video gaming.

The Chaos Sanctuary, Diablo II

It's a long haul to Hell, that's for sure, and after chasing Big D across damn near the entire known world, all you want is his blood. But you can't have it. At least, not right away. He's still got minions a-plenty, and some of the most irritating kinds in the game. Heavy hitting physical/fire damage combos, mana-sucking casters that run away from you and cast again, and oh yeah -- anybody like wielding melee weapons? Try it. I dare you.

Once you make it past the Iron Maiden-casting Oblivion Knights (or perhaps if; I've heard of people quitting the game because of those guys), you still have to deal with Diablo's super uniques -- the Grand Vizier of Chaos, Lord De Seis, and the Infector of Souls, plus their minions. Each is tuned slightly differently so as to offer challenges to various character types (the Infector g

enerally proves hardest for me because he's so obnoxiously fast). Then, at last, when the countless hordes lie dead about the Sanctuary, the ground shakes and Diablo at last shows himself, uttering possibly the most badass taunt ever thrown at PC gamers: Not even death can save you from me. After which, he proceeds to roast you alive with the dreaded Lightning Hose -- the near-instantly lethal attack that has provoked an indignant "AWW, SHIT!!" from me more times than I can possibly count. Regarding town portals: cast early, cast often.

enerally proves hardest for me because he's so obnoxiously fast). Then, at last, when the countless hordes lie dead about the Sanctuary, the ground shakes and Diablo at last shows himself, uttering possibly the most badass taunt ever thrown at PC gamers: Not even death can save you from me. After which, he proceeds to roast you alive with the dreaded Lightning Hose -- the near-instantly lethal attack that has provoked an indignant "AWW, SHIT!!" from me more times than I can possibly count. Regarding town portals: cast early, cast often.All in all, this battle with the Lord of Terror is one of the most memorable not only because of the skill, patience, and versatility required to get through it, but also because of the sheer build-up to this moment. A deliciously dark fantasy world complemented by great cutscenes and tense, addictive gameplay makes this showdown a satisfying (semi-)conclusion to one of the most popular RPGs of all time.

Batman vs. every last incarcerated criminal in Gotham City, Batman: Arkham Asylum

I have been waiting for a good Batman game since I was three years old, when I saw Tim Burton's film with Michael Keaton and Jack Nicholson for the first time. And at last, we have a great Batman game. I can't recall the last title I've played (if there is one) in which I had so much fun kicking the tar out of so many enemies all at once.

It's on my Showdown list for a couple reasons. For one, the game does a fantastic job in making you feel utterly alone in the looniest loony bin on Earth, and that you are really, truly the only thing standing between Gotham and total chaos. And secondly, because every single encounter with the Joker's thugs was so thrillingly, perfectly Batman, whether I swept through the shadows and hung them upside-down from gargoyles or just strolled right up and smashed all their faces into the pavement.